Turbocharging product development

In the eternal debate over in-house teams or external agencies, everyone is obsessing over the politics of either-or, when they should be…

In the eternal debate over in-house teams or external agencies, everyone is obsessing over the politics of either-or, when they should be focusing on the end goal: the best possible services. And that can only come from an intelligent combination of both.

by Mark Wilson, Founder Partner, Wilson Fletcher

Years ago, our engagement with clients was simple. We executed the task in hand before handing the result of the project back over the the client once it was complete. Now, the way we work together is changing. As the capability of in-house teams has grown, so too has the potential for how design partners can work together with them.

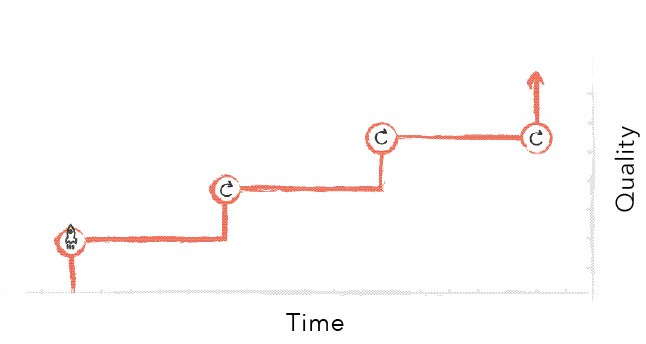

Outsourced step-change

For years, we worked with clients as an outsourced agency. We undertook periodic design ‘updates’ to their sites, apps and services. We’d conduct a rigorous design process and deliver a step change in that service’s performance.

The pattern of a service’s development looked something like this:

The net result was that over time, the service progressively improved. Each major design update gave it a new lease of life, and by involving customers in that process, we could at least ensure that it was fuelled by genuine customer insights. That, alongside some evaluation of performance data, got us as close to the customer and the operational realities of that service as we could get.

In the intervening periods, nothing much changed. Our clients ‘ran’ their services based on the last design update. They invested little in them and rarely made the incremental changes that can only come from understanding the behaviour of a service and its customers on a day-to-day basis.

It probably appeared to customers somewhat like the way cars are still released into the world: interim refreshes are released fairly frequently to maintain competition and sales performance, with major new model releases every few years to reset and reposition with a big splash. Over a decade, each car model gets substantially better — by way of relatively big steps, taken relatively infrequently.

Except, unlike cars, digital services need to adapt much more frequently and are subject to an infinitely more complex set of competitive and behavioural influences, in much shorter timeframes.

To respond to the nuances of those influences — the small changes made frequently — you need to be close to the service day in, day out. Today, that role often falls to product owners or product managers.

We often used to nag our clients to hire in-house teams; to take ownership of their services and to see them as living entities, not static operational releases. They needed to own their own products.

We knew that we, as an external partner, could never play the role of product owner — nor should we. We declined retainer-based relationships on that basis, as we knew we’d be bad at them: we simply would not be close enough to the performance of the service concerned, or integrated tightly enough with the operations of the organisation that owns it, to make frequent, iterative changes. Our role was to facilitate the big steps.

In-house evolution

Over the last decade, we’ve seen a slow, steady increase in the number of organisations who have hired in-house UX/design/product teams, to the point where now there’s almost a ‘mine is bigger than yours’ competition going on among peers. But politics aside, organisations now realise the importance of evolving their products in response to continuous market movements, and have invested in bringing those skills in house.

There are now, finally, teams in place that can deliver steady, incremental improvements to products and in many cases they have an influential seat at the leadership table too. The development of a typical product now looks like this:

The big advantage this has over the old model is that there is no hiatus period between launches. Even though the peaks are not always as high at a single point in time, customers get continuous improvement to their services (when the product team works well of course) and you can certainly argue that as a result it leads to a better customer experience over a given period of time.

Great internal product teams get really close to the needs of the customer and organisation and respond to them quickly and continuously. They can act to address a slight decline, to respond to a competitor’s new feature and to capitalise on a success. Their closeness to their product allows them to optimise and refine it in ways that we, as an external partner, could never do. No matter how well we know the product, we’re simply too detached from its day-to-day to deliver that kind of continuous incremental change.

We learn something new from each team we work with, and our involvement always leads to an acceleration in the continuous part of the graph too.

The change this has brought about is an overall lifting of standards across whole sectors: customer experiences get better on average as multiple organisations iterate their products more frequently in response to each other. Look in almost any established sector that has built in-house capability and you’ll see an overall increase of experience standards.

Competitive convergence

And that’s where things are getting interesting. That pattern is leading to smaller margins of difference between competitors: they are becoming more and more alike as they learn more and more about a typically shared or similar customer base — and each other. Standards seem to rise in almost direct correlation with similarity, and that’s starting to cause all sorts of new problems, most of which should be blindingly obvious. Put simply, it’s harder to differentiate when the differences are — in every sense — small. And it’s also progressively harder to step back far enough to see how.

Think about any established digital sector these days and you’ll see this playing out. Price comparison, flights, travel, ticketing, gambling, restaurant booking, messaging, property… the differences between services in any given sector get progressively smaller as they become more evolutionary in their approach.

Ironically, it’s a flaw borne as much of customer-centricity as it is an obsession with peers. In any given sector, customers are most likely to be able to articulate differences based on their preferences from other services in the peer group. “Their calendar is much easier to use”, or “I like it. It’s more like theirs and I think theirs is the best” are two of a thousand similar ‘insights’ that are gleaned every day from customer research that are fed into incremental design improvements, and consequently to increasingly convergent experiences across competitors.

Let’s think back to the old stepped model for a moment. Interestingly, it didn’t suffer from this problem. For its weaknesses in continuous improvement, it did allow organisations to assert their difference more effectively, at least for a period of time. Each time we worked on one of those big step releases, we came to it with fresh perspective (not least because we’d worked on a variety of other things in the interim) and could often see both gaping flaws and glaring opportunities that could be capitalised on.

Both approaches work for some things, and fail for others.

Turbocharged evolution

Fortunately for all of us, there’s an obvious answer. The more enlightened organisations are realising (to be fair, some always knew) that this is not an either-or choice. They’re recognising that the only way to build any form of substantive market advantage is to combine both.

Instead of comparing the stepped approach against the continuous one, look at what happens if you combine them effectively.

It’s really not rocket science. Combine the two and you end up, at any given point, far ahead of either approach in its own right. Step-changes are like a turbo boost for product evolution in the same way that periodic ‘mutations’ are increasingly believed to lead to major acceleration phases in biological evolution — albeit in rather less predictable ways.

In mature sectors, this is common. Car companies buy in external design studios frequently to help their (often very talented) internal teams challenge assumptions and take bolder steps forward. Technology hardware companies run large in-house teams and buy in design at some of the highest levels of any sector. FMCG companies have long had external creative teams, whose help they buy in for major refreshes or launches.

Imagine how many large corporations there are today with equally large, expensive in-house corporate legal teams. You’d be hard-pressed to find one without some external firms on retainer. In fact, the modern generation of powerhouse legal firms of today (think Suits) only emerged after Jack Welch started the in-house revolution by hiring a heavy-hitting legal team at GE in the 1980s.

Using both internal and external teams, unsurprisingly, beats selecting one or the other.

The age of the sophisticated buyer?

From our perspective as an external partner, it’s easier for us to facilitate step changes if there’s a great in-house product team in place: we can get closer to the product faster, and can gain enormously from the experience that team has working within its organisation on a daily basis. Those insights can spark all sorts of new ideas in our team and we can short-cut all sorts of dead-ends without losing the value of our role — to bring a broader perspective and a different mindset to bear on the same challenges. We do our best work alongside great in-house teams, because they only get to be great when they realise that we each have a role to play that the other can’t.

Unsurprisingly, the benefits go both ways. We learn something new from each team we work with, and our involvement always leads to an acceleration in the continuous part of the graph too. Even when we work with the most accomplished in-house teams, we’re able to leave them with some new techniques, new tools to think with, or insights from other sectors that enable them to do their own work better.

Perhaps we’re finally at the point where the more progressive organisations are going to capitalise on the potential presented by an effective internal-external collaboration. Having seen in-house teams bed-in over the last few years, growing in their own knowledge and confidence in turn, organisations are at a point where they can approach digital expertise exactly as so many mature sectors have approached external support before them.

After this period spent building internal capability and getting overall standards up to scratch, I believe we’re heading into an era of greater leaps in the digital products and services we all use again. This will be an era of greater focus on differentiation and, dare I dream it, more confidence in the value of design and its role in commercial success.

This article was originally published by Mind the Product: http://www.mindtheproduct.com/2016/04/turbocharging-product-development/